One day in February 2020, as I drove alone through sunshine and a landscape of winter trees, this song—Off You by The Breeders—began to play on my car stereo:

I don’t know where it came from since I’d never heard it before, and I had autoplay disabled. But somehow this one song snuck through a crack in the universe and found me. It’s hard for me to say how or why, but this song cast a spell on me and changed me.

I’ll try to make sense of it: the song felt slow, tender, and deliberate. It felt like a balm. It felt weary. It felt wild. It felt like all the things I felt and also all the things I wanted to be.

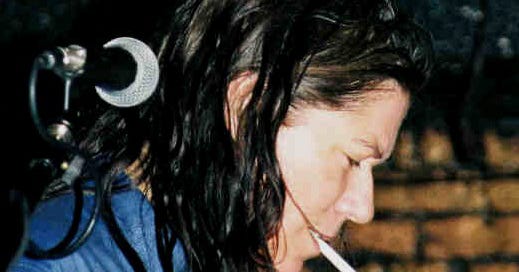

When I got home, I traced the song back to its album, Title TK, released eighteen years before, in 2002. I had loved The Breeders in the nineties. I had, as a teenager, snuck into a show I was too young to be at just to watch them play two songs before catching the last bus home. But when the nineties ended, I stopped following them, assuming their best work was behind them. Also, for a while, I stopped listening to almost anything. Adulthood was demanding and I didn’t think I needed music anymore. But nearly thirty years after sneaking into the Paradise for a glimpse of Kim Deal, I fell in love with Title TK, a strange and beautiful album that is unapologetically spare.

I don’t need to tell you what happened next in 2020 because you were there too and you remember. My version included waking at 5 to clock work hours before my children needed me, leading Zoom meetings in a random corner of the house where the internet was stable, muting myself to help my 7-year-old troubleshoot a Minecraft issue, and shouting through a locked bathroom door to communicate with my newly adolescent older son. I was forty-three years old and, as weary as I had felt in February, I felt far wearier in March.

To cope with those early months of lockdown, I bought myself a set of earbuds and escaped for a run every morning with Title TK in my ears. Before then, when I ran I always disciplined myself to listen only to my surroundings, but now I needed a bigger escape—I needed sound to fill my whole body and push me through my route. I needed Kim Deal’s voice piped directly through my ear canal.

As I ran, I thought so often about Kim Deal, who was in her early 40s in the year that Title TK was released. I felt palpable relief at this—it was a feeling that accompanied each step of my run—that aging didn’t have to mean creative deterioration. That even in the world of rock and roll, getting older didn’t mean you had to become a caricature of your former self. There are plenty of artists who stop growing once they achieve some measure of success or see their youth fading in a trail behind them. But Kim Deal continued to do the work.

If you hop on the Wikipedia page for Title TK, you’ll see that the process behind that album was a shitshow, perhaps more of a Kim Deal project than a true Breeders project, since musicians kept quitting over Deal’s exacting standards which didn’t mix well with her active addiction. Deal has said that she recognized herself in the adage: “I wasn’t a musician with some drugs in the room, I was a drug addict with some musical gear in the room.” She went to rehab the same year that Title TK was released and by all accounts has remained sober since. I confess, I take deep pleasure in knowing that in the throes of addiction, Kim Deal pissed people off with her high standards—that even the shadow version of Deal is someone who’s ruthlessly married to sound.

Two weeks ago, Deal released her first solo album, Nobody Loves You More. I awaited the album’s release date with more fear than excitement. I wanted Kim Deal to keep coming through for me, and I know that sometimes we expect too much from the people we admire.

In this profile for The New York Times, we learn that the songs from this album grew out of Deal’s experience of giving end-of-life care to her parents in Dayton, Ohio. The album is tender that way. Deal’s voice is (as ever but perhaps even more so) sweet and broken. The opening tracks are rhapsodic and symphonic in a way that differentiates Kim Deal as a musical project from The Breeders as a musical project. The opening track plays as a big swoon of grief and love. Somehow, like all of Deal’s best work, it manages to be both vulnerable and polished, and the song itself feels like standing on the precipice of loss and change.

Deeper into the album, we encounter Deal’s familiar fierceness. The track Disobedience is the anthem I need to carry me into 2025, especially the moment where Deal sings “If this is all we are…I’m fucked.” There’s nothing better than a hard R sung by Kim Deal, or a guitar riff coming in strong after a pause.

Deal sings “I go where I want while I’m still on the planet,” and goddamn, I hope I can follow her. Hers is a path where tenderness and fierceness live in symbiosis. It’s also a path where she’s releasing her solo debut at 63, and I find those words, debut at 63, so beautiful to write. To think: you can have an iconic career; you can change the landscape of rock, you can get sober, buy a house in Dayton, and take care of your parents as they leave the world. And then you can make your debut.

Quick announcement:

I’m taking on a small number of clients for coaching and editing services. My practice is based on many years of writing and teaching and values around working with trauma and neurodivergence. My rates are designed for accessibility. You can learn more about my practice here, and contact me to schedule a free 20-minute call.

Kim Deal is life!

Thanks too for new music to experience.