Microchimerism: I'm in My Mother, and My Mother's in Me.

(and also my children, my brothers, my sisters)

During last week’s Joyful Practice session, Jenn introduced a new idea she’s been gestating–a taxonomy of feedback that offers a somatic approach for engaging with writing and what it wants to become. One important tenant of Jenn’s taxonomy is recognizing input from our bodies as a form of feedback, both while we are writing and when we are reading.

For example: right now, my body feels agitated and impatient. Get on with it already, my body says. I want to write about how the cells of my mother are likely still inside of me, and how the cells of my children are almost definitely inside of me.

This morning, I couldn't grade. I’d look at the screen and zone out. I’d start reading an essay and feel overwhelmed with exhaustion. So I took a nap instead. The rest did not help me focus. It only made me more agitated and anxious about the ungraded essays waiting around for my attention. There are so many other things I could be doing, like the list of garden tasks still unfinished, which also makes me feel exhausted and overwhelmed. No surprise, the pressure to do the things I should be doing is not (yet) as strong as the desire to do the things I want to do.

I’ve now entirely given up on grading and keep wandering back to the database searches I opened up this morning on microchimerism (when I was only toying with the idea of putting off grading). Microchimerism happens when cells from a different genetic origin are found inside a woman’s body. Tiny amounts of microchimeric cells have been found in kidneys, brains, hearts, and, of course, placentas and umbilical cords. Microchimeric cells seem to exist quite happily inside their host’s body and can potentially help with some types of healing (except when they maybe sometimes might create autoimmune diseases or even cancer). I’ve spent the afternoon digging into academic articles with names like “Pregnancy, Microchimerism, and the Maternal Grandmother” (if you want to learn more about how women who carry their mother’s cells are less likely to have preeclampsia during pregnancy, this study is for you).

Most of the articles I’ve read refer to microchimeric cells as foreign. I even saw one researcher call them alien cells. Most pregnant people who’ve felt their baby moving in their womb, or watched early ultrasound images of a somersaulting fetus, understand the eerie sense that something alien has taken up residence in their body. I laughed out loud when I first came across a study referencing the cells of a woman’s mother or son as foreign. Because they are. But also, they aren’t.

It isn’t just pregnant people that host microchimeric cells. One article describes microchimerism as cell trafficking between a mother and child. This means that my son might be carrying my cells in his body. In a Scientific American article from 2012, Robert Martone explains how microchimerism happens: “Microchimerism most commonly results from the exchange of cells across the placenta during pregnancy, however there is also evidence that cells may be transferred from mother to infant through nursing.” Two pregnancies and almost eight years of nursing means that there’s a pretty good chance I spent the majority of my twenties exchanging cells with my children. This idea gives me solace. When I imagine our cells bobbing about in one another’s hearts and brains, I can start to make peace with the physical ache that manifests anytime I start to miss my children and the acute sense of longing that doubles me over if I think too hard about the recent distance between my eldest and me.

My heart rate picks up, and I find myself leaning towards the computer screen when I read this from Martone’s article: “In addition to exchange between mother and fetus, there may be exchange of cells between twins in utero, and there is also the possibility that cells from an older sibling residing in the mother may find their way back across the placenta to a younger sibling during the latter’s gestation.” Holy fuck. I hope the twins, my younger brothers, share cells–how could they not, after months spent curled up together in our mother’s womb, passing nutrient-rich blood back and forth. Maybe my cells are somewhere inside my brothers? What if Mari, our baby sis, has cells from all of us? And my stepsister’s cells might be hanging out in Mari, too.

I feel a weight on my chest every time I use the word step to describe our middle sister. It’s like using the word half to describe Mari. Or Lily, our sister who died, who was also technically a half sibling to all of us except Mari. I wish there was some kind of sister-osmosis, so our middle sister and I could exchange cells. When someone holds your history and your heart, you are wholly family–no steps, no halves.

But wait–eyes wide, an involuntary yelp, and my hand moves to the top of my head: it isn’t a stretch to think that some of Lily’s cells took up residence in our mother’s body and emigrated to Mari through the waterways of Mom’s placenta. That means some little part of Lily might be held by Mari.

When I think about that, I smile and the weight in my chest feels a little lighter. My body is telling me it's time to stop writing. It wants to pee. It wants to cry.

I keep thinking about a question Jenn offered up at the end of last week’s Joyful Practice session:

How do we take care of ourselves when we write?

Today’s answer: I walked away from the words on this page for two days. I could hear the whispers of ideas I’d read long ago about cyborgs and monsters and chimeras. I needed to seek them out, to see if they held any answers or asked any important questions (I think they might, but this is beginning to feel like another saturation job and is way beyond the scope of a 1,000ish word post).

Mostly, I needed to let the ideas in this post sink deeper into my body. When I close my eyes and imagine the cell-swapping-square-dance that is microchimerism, in the very center is the desire to stay connected to those I’ve lost (or fear I will lose).

I want to know for certain that because my cells are inside of them, my eldest will somehow find their way back to me. Maybe we will find a way to understand one another’s hurts and betrayals.

And also if some tiny, tiny part of my mother resides somewhere inside of me, then that means there is a speck of Barbara Jean still alive. Maybe that part of her that is inside of me can find some of the acceptance and peace that I suspect she did not find inside her own body.

And Mari holding Lily’s cells in her body. I can hardly comprehend a world where there is even the smallest bit of Liy not inside a concrete hole in the ground. Just the idea that a part of her that came from a part of our mother might exist in this world–my body wants to cry again, and I am definitely smiling.

When I sat down to write this post, my plan was to follow Jenn’s taxonomy of feedback and listen to my body. I didn’t expect to open what Jenn called, “a fucking portal to grief and art.” But here it is, waiting for me when I’m ready for it. Another saturation job. When I look back over the past two years of Scrap Heap posts, I realize that our newsletter is more than just a conversation between Jenn and I about grief, healing, and the creative process. It’s more than the Joyful Practice work we are sharing with our community. It’s become a kind of basket to hold big ideas until we are ready to go where the ideas want to take us.

comments are open

I’m curious what you think about this question, how do we take care of ourselves when we write? This question is important to consider for any creative endeavor, and really, we should keep it in mind whenever we engage in any type of deeply vulnerable practice. I’m thinking about the act of caretaking, or pushing our bodies’ edges through physical activity, or having hard conversations, or engaging in activism, or reading the damn news.

Maybe another way to ask this question is simply:

How do we take care of ourselves?

How do we take care of ourselves? The question itself is an invitation. I think somehow creating intention before writing. Or an awareness. Checking back in with yourself at times to notice the feedback. Redirect. Acceptance. Having times to be validated and held up by others could be good scaffolding. I think I've never thought about this question until now. I like thinking about it. I'm curious.

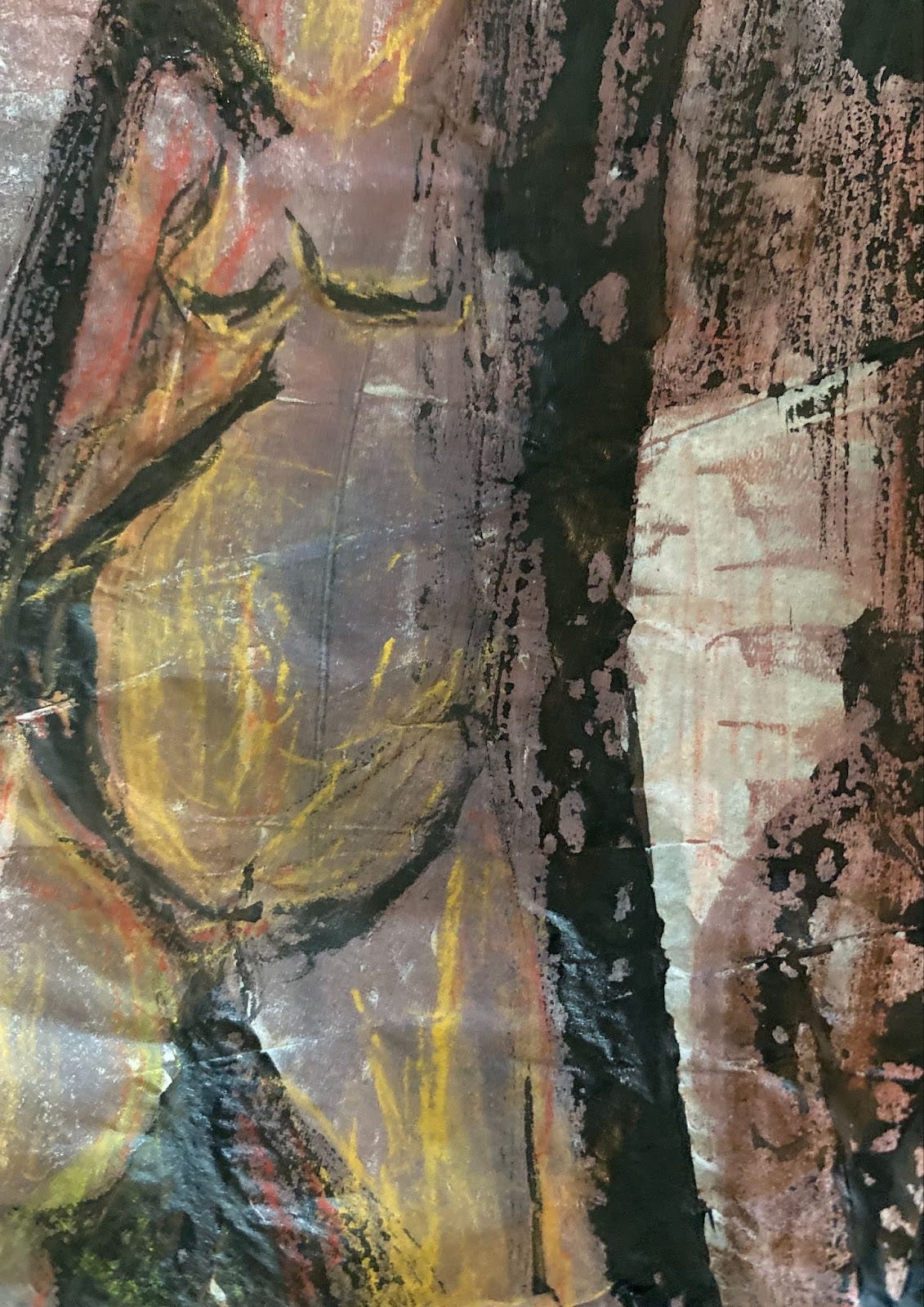

So much is swirling in my mind and heart right now. First off, a question: did you do these touch drawings?? They are beyond beautiful, beyond amazing, so I was curious about the artist.

Second, a dear old friend who was the first person I told about Rachel’s death was a nurse practitioner. She told me on that day about this idea of how cells are retained in the umbilical tissues, and that Rachel would be there, at least on a cellular level, all the days of my life.

At the time, this provided little comfort, but now, all these years later, it actually does.

Thank you, Sarah. We are all here, everywhere, all together, forever.