Orca Burdens

Tahlequah in her own language

Content Warning: Maternal Loss

-

A newborn orca calf weighs about 300 pounds.

In 2018, Tahlequah, an orca who lives in the Salish Sea, lost her baby. Lost, as in: the calf died.

Tahlequah wouldn’t allow her dead calf’s body to sink to the floor of the Salish Sea. Instead, she kept her afloat—by nudging it, by carrying it, by enlisting the help of her pod mates. She did this for seventeen days, for a journey of a thousand miles. Researchers feared for her health. Tending to the calf’s body required great physical exertion with little food and rest.

After those seventeen days, what Tahlequah had worked so hard to delay finally happened: the letting go, the final plunge of weight through water, both the life and the body Lost.

This past December, just before the new year, Tahlequah was seen with another newborn calf—another female. For a few days this was joyful news. Tahlequah is part of a special population of orcas, the Southern Residents, who are federally endangered. Orca culture is matrilineal, and Tahlequah, 25 years old, the oldest female member of her pod, is its leader. A female calf brings a special hope for future reproduction.

But only a few days later, the new calf had died. Together, those of us watching the story worried about the next turn this story might take, and then it took that turn.

Two days ago, on January 10, The Seattle Times reported that Tahlequah was spotted again in Haro Strait, still carrying her calf after 11 days.

Tahlequah is the name that humans gave this mother orca. All Southern Resident Orcas have nicknames. The practice began in the 1970s during what is now known as the “capture era,” when orcas were trapped in nets and sold to marine parks. Conservationists believed that assigning a name to each orca would help humans connect to them emotionally. It worked, and the practice continues. Naming this whale Tahlequah has invited us to connect more deeply to her story. She is at once an orca, a resident of the wild, but also, because we have named her, she is our pet.

Tahlequah’s scientific name, assigned for tracking purposes, is J35. But neither name—not her nickname nor her scientific name—is what this orca calls herself.

Orcas have their own language. Researchers believe that they have signature calls— a sound they make to identify themselves. In other words, they sing their own names as they move through the water to be recognized by their kin. If this is true, then Tahlequah has her own name for herself, one that humans can’t pronounce.

In the last weeks, I’ve seen Tahlequah’s story discussed as a cry for help and a call to action because orcas are suffering at the hands of human destruction in the forms of: dwindling salmon populations, heavy boat traffic, and water pollution. Many of us speak of her tour of grief like it’s a performance designed to call us to action. Sometimes, when animals engage in rituals we recognize, we act like they are more worthy of our consideration because they are like us. We project our humanity onto them rather than understanding them on their own terms. But orcas don’t have humanity. They have orcacity.

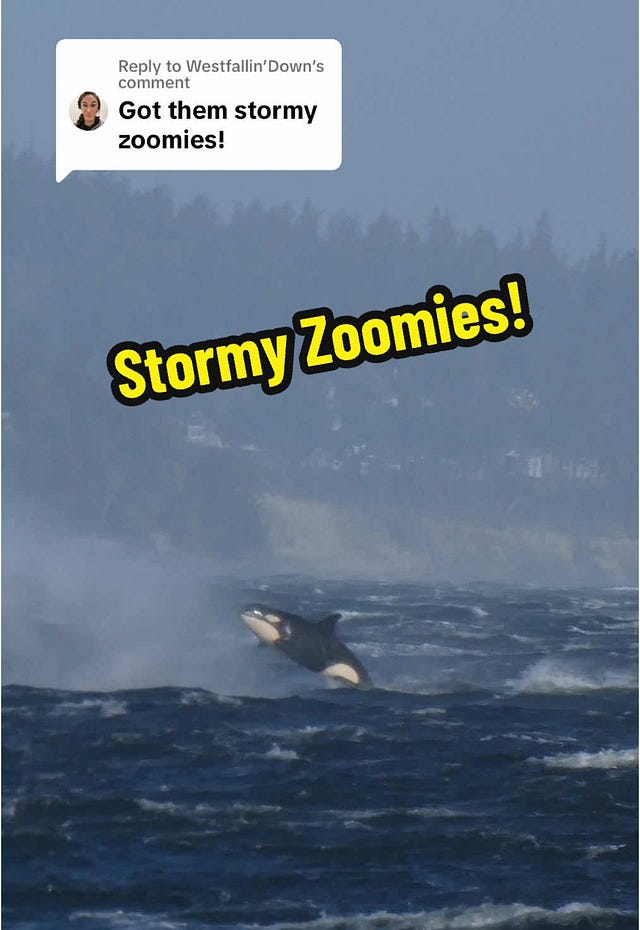

And Tahlequah is more than a symbol. She is not performing for us. She’s an orca engrossed in an orca experience of grief. Her suffering exists even when we’re not watching. In this era, the orca experience is one of great joy (see below) but also great deprivation.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

One of the reasons the Southern Residents are endangered is because of their cultural practices. They eat salmon. More specifically, they eat Chinook salmon, which were once abundant in their waters. Other orca populations eat other things, like seals and squid and even whale sharks, and those with a flexible diet have maintained higher numbers. But the Southern Residents hold to their traditions. I’m not anthropomorphizing them when I say this. Orcas maintain a rich and meaningful culture. It’s not a human culture.

Sometimes I dream of the world, pre-colonization, pre-industrialization, when animal populations thrived on their own terms. I dream of the abundance of such a world: landscapes unmarred by roads and fences. Humans as small dots in the wilderness.

Sometimes I wonder about a future world, maybe an impossible world, where humans are mere participants in an ecosystem rather its reckless rulers. The lush grasses restored. The forests forever old growth. Salmon filling the creeks.

In such a world the orcas will still know grief, just as the humans will still know grief, because grief is a part of the orca / the human experience.

But in such a world, the orcas get to be orcas and not symbols. There will be so many of them, we won’t have to name them. They won’t have to carry our burdens.

Update: we are still open for registration for our 8-week virtual (Zoom) workshop: Joyful Practice in Dark Times. You can learn more at this link. Space is limited. We’d love to see you there!

Moving, haunting, heartbreaking. Thank you for your words and bringing this compassionate perspective.

Have you listened to The Good Whale podcast? It helped me understand more about the Capture Era and what humans have done to orcas. Also, Kathryn Schulz's piece on animal grief was incredible: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/11/04/playing-possum-susana-monso-book-review