Sometimes I pick up my phone to check the time, but then a notification awaits me and sucks me deep into the apps. After a while I extract myself, put down the phone, and then I realize that I never checked the time.

My phone does so many things; it has replaced so many analog objects—beautiful artifacts that only do one thing. There is a deep loss in this.

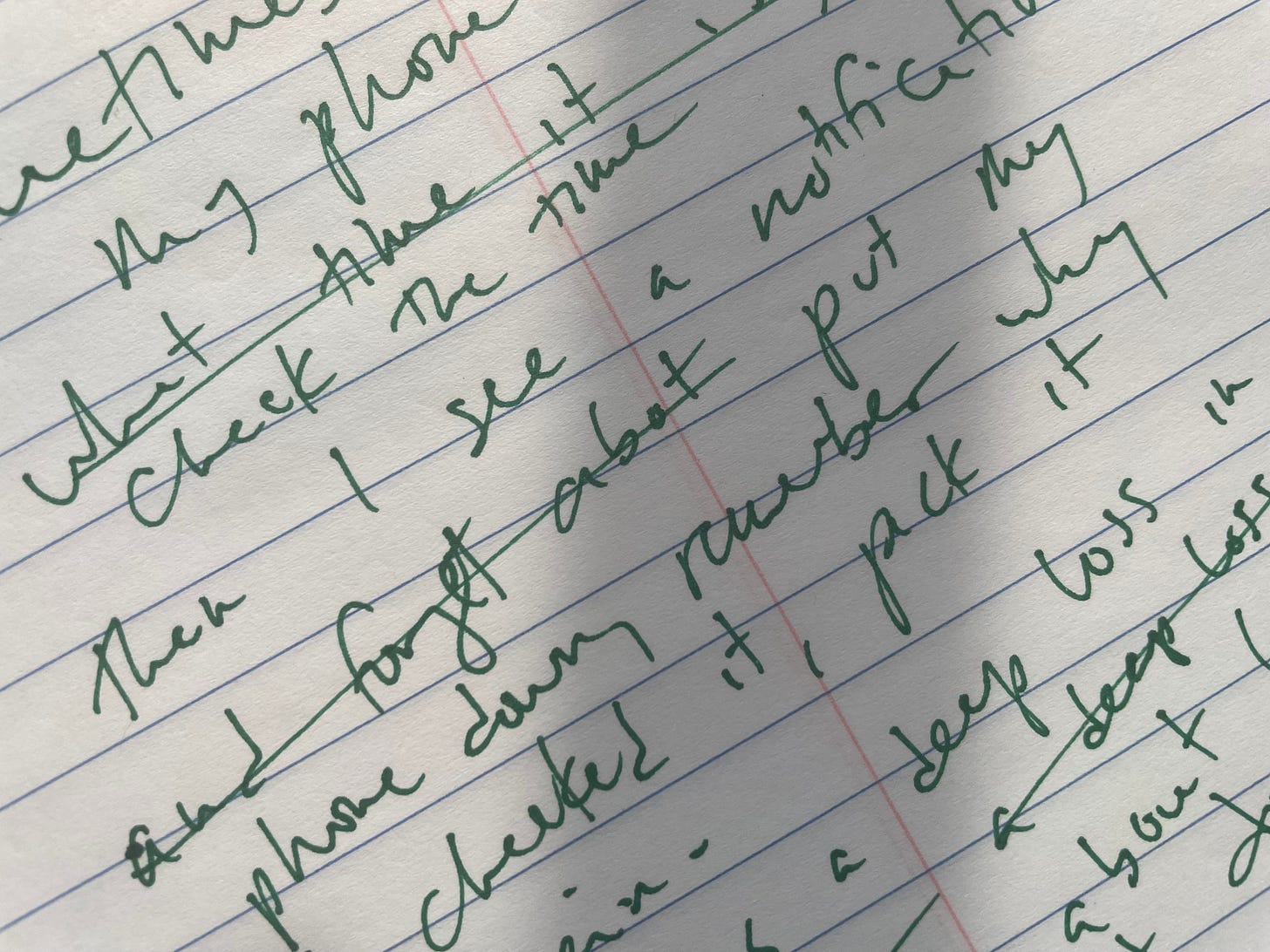

In my young adulthood, I wrote by filling notebooks. What was writing to me then? A place to put thoughts so that they didn’t have to rattle in my brain forever, and then once in a while, a poem. Eventually, when I decided I wanted to be serious about writing, I bought my first computer. One of these:

That computer was little more than a container for my words, a place to store short stories that I wrote in a new way: poring over, leaning in, looking out the window, tinkering. I could get on the internet if I wanted to, but it was slow, and I had to sit through that terrible noise—the handshake of the modem connecting to the phone line, and so mostly I just wrote.

In an recent post, I mentioned the Microphones’ 45-minute song, Microphones in 2020, in which Phil Elverum (the man who is the Microphones) tells a kind of coming-of-age as an artist story, charting through music “this river coursing through my life, these wild swipes at meaning.” Much of the song takes place in Olympia, WA in the early aughts—the same place I lived when I was typing on my bubble-shaped iMac. (Still here, still typing.) There’s a certain eeriness to hearing a stranger describe in intimate detail a terrain you hold in your heart. (Do you actually know the stranger? Do you actually know the place?)

Anyways, there’s this line from the song that keeps haunting me:

I checked theMicrophones-at-hotmail-dot-com, like, once a week.

Such a world in that one line. A world where the internet existed only as a distant novelty—a situation that sits in clear relation to the following line:

I would drive out to the ocean and not tell anybody

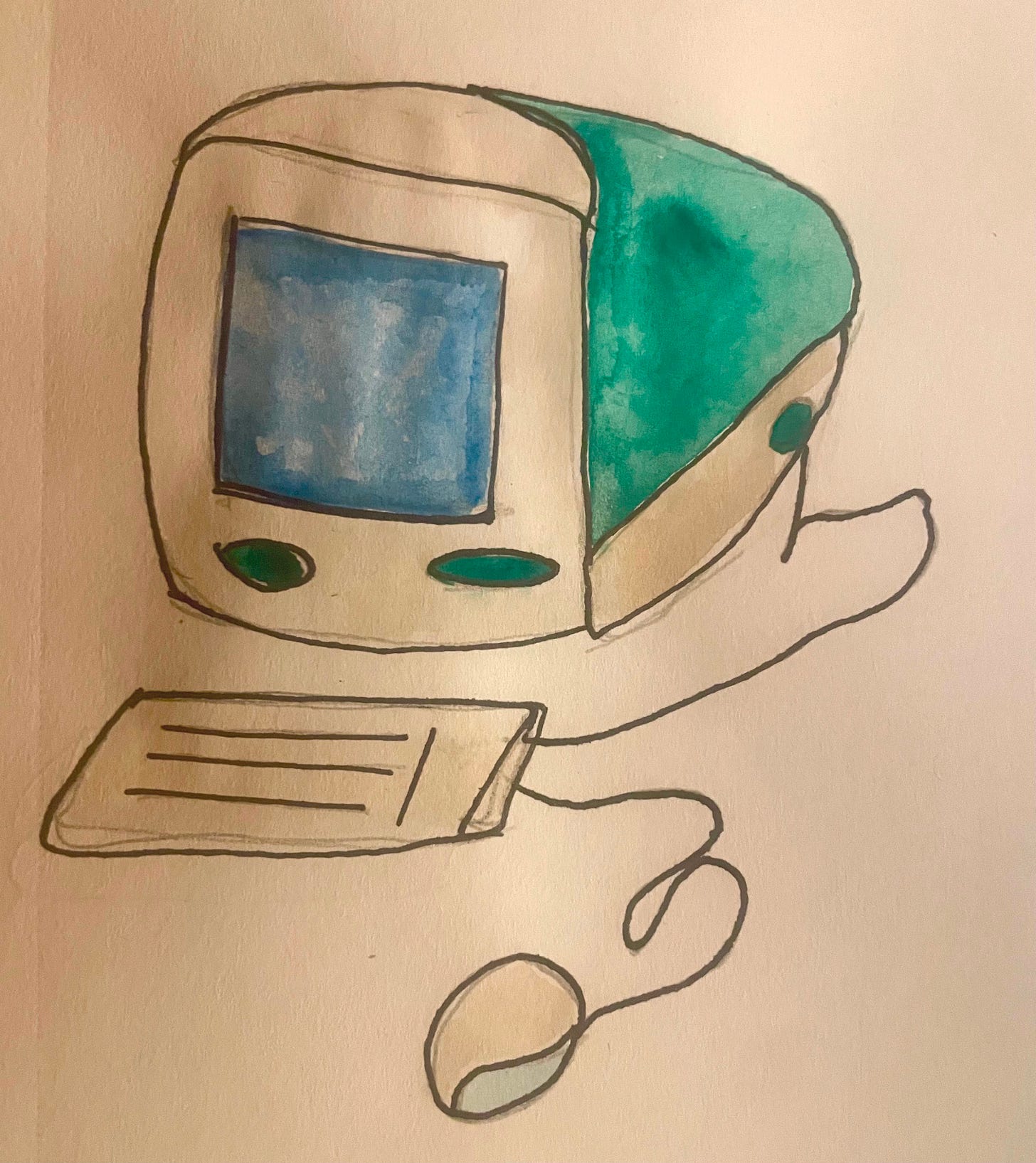

To write this post, I set a timer on my phone for ten minutes at a time to help me focus. I no longer own an analog timer. I used to have multiple. Where did they go?

To write this post, I wrote by hand ten minutes at a time. I’ve been dreaming of a time before the word processor, a time when you’d write a draft by hand and then you’d type it on the typewriter. Maybe an editor would write in pen around the typing. I’ve been dreaming about how those limitations would change the process. How would I write if I had no digital distractions? But also, how would I write if, to move paragraphs around, I had to cut up pages with scissors? And how would I write if I couldn’t endlessly tinker?

Right now, as I type this into scrapheap-dot-substack-dot-com, loosely copying from my earlier draft, I’m trying to pretend I’m at a typewriter. I type slowly as if I were using ink and whiteout ribbon, as if each letter I laid down were a tiny commitment. But as I type, my phone is pinging me, and my computer talks to my phone, and so my computer too is pinging me, both of them announcing an non-urgent message with great urgency. I can’t maintain the illusion of an analog process.

But still, this post started as a hand-written draft, and I wonder if you can feel that? I wonder if analog thoughts are different from word-processed thoughts. I wonder if you can can feel my hand moving across the page, the smear of ink on my right pinky.

Analog Challenge

Please tell me about the analog objects you refuse to replace.

Tell me about how analog practices are part of your creative process. (Or tell me the opposite—tell me about the doors the digital world has opened.)

This week and beyond, I’ll be experimenting with keeping drafts analog (pen on paper, highlighters, scissors) for as long as possible.

Comments are open below.